The earnings of PhD candidates vs. other master’s degree holders

Becoming a scholar demands diligence and sacrifice. In most cases, the first step on this path is the commencement of doctoral studies. As PhD candidates focus on their theses, research, publications, and other related activities, they are typically unable to compete on the labour market successfully. This short commentary explains what young scholars have to deny themselves in terms of their economic circumstances, as well as the differences between their position on the labour market and that of their peers who have opted not to pursue doctoral studies.

Our analysis concerns the individuals who completed master’s (second- or long-cycle) programmes in 2015 and 2016. The 7th edition of the ELA report presents data on the circumstances of these two cohorts during the five-year period after their graduation. It compares the achievements of the 2015 and 2016 graduates who were PhD candidates for at least three years with those of other master’s graduates of the same years.

We utilise the relative earnings rate in our comparison. This allows us to juxtapose the graduates' earnings and the average earnings in the Polish powiats where the subjects of the study resided during the monitoring period. The relative earnings rate enables reliable comparisons across time and space, regardless of changes in earnings across Poland and differences in earnings by region. The relative earnings rate is easy to interpret: if its value exceeds 1, the earnings of the specific individual to whom it pertains are above average.

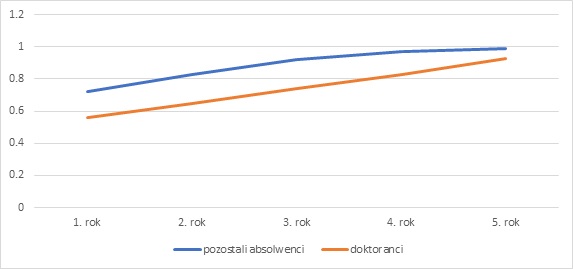

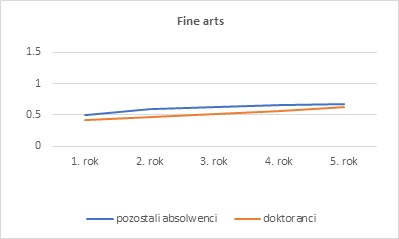

Figure 1. The relative earnings rates for 2015 and 2016 master’s programme graduates during the first five years after graduation: PhD candidates vs. other graduates.

The earnings of the PhD candidates were lower than those of other master’s programme graduates. It is worth noting, however, that the earnings of young scholars rose at the same pace throughout the monitoring period, while those of other graduates failed to increase as steadily. As a result, the pay gap narrowed from 16% of the local average earnings to 6% five years later. A more detailed explanation of the nature of this change was made possible by related analyses of individual fields of study.

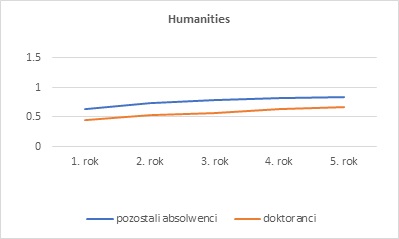

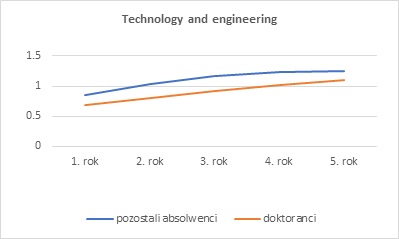

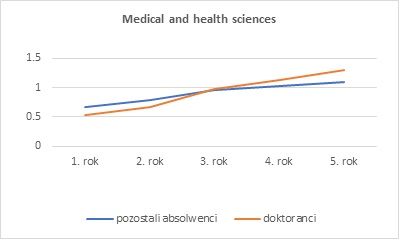

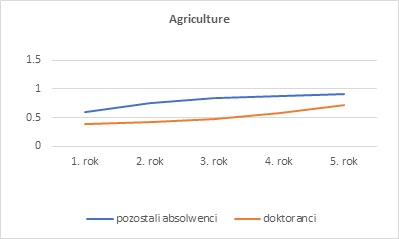

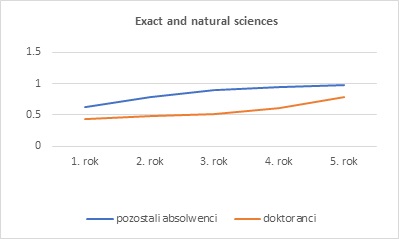

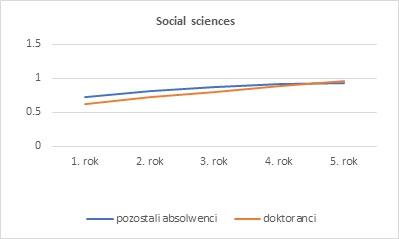

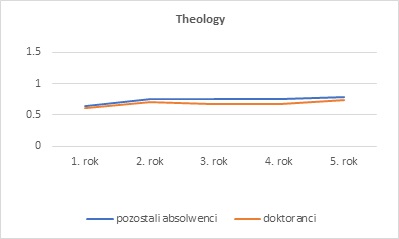

Figure 2. The relative earnings rates for 2015 and 2016 master’s programme graduates, by field of study, during the first five years after graduation: PhD candidates vs. other graduates.

Compared to other master’s graduates, the earnings of PhD candidates who majored in the humanities, technology and engineering, agriculture, and exact and natural sciences are substantially lower.

Among graduates of theology and fine arts, PhD candidates earned only slightly less than other diploma holders.

Particular attention should be paid to the circumstances of the graduates of social sciences, and of medical and health sciences. In these domains, the earnings of young scholars have recently been higher than those of other graduates: by 3% of the local average earnings in the case of medical and health sciences, and by 19% in the social sciences, in the fifth year after graduation.

Despite the necessity for young scholars to sacrifice higher earnings in pursuit of their careers, some of them may hope in the future for more tangible benefits in addition to professional advancement.